© 2025 Berryworld, All Rights Reserved

Lessons from the past, Installment 2: Soil Health

There’s a 2004 booklet titled “Soil quality monitoring for blackcurrants in Canterbury,” produced by a team from Crop and Food Research. The group surveyed soil health in 33 blackcurrant blocks in Canterbury. The following is a summary of that 2004 work.

While photosynthesis in sunlight is the energy source for plant growth, roots take up the required nutrients and water, and therefore are the key determiners of what growth the plant can achieve. If photosynthesis is like the petrol that feeds the engine of your car, then the roots are like the rest of the car body and wheels combined—fundamentally important to getting you where you want to go.

Soil Health matters because it largely determines root health. Good soil health enables abundant and active root growth, supplying minerals and water to the shoots. The shoots, in turn, photosynthesize and supply carbohydrates into the roots, enabling their growth. Lots of roots growing and leaves going back to the soil feed the soil organisms that create good soil structure. It’s a virtuous cycle.

Surveys of soil condition in the early 2000s in Canterbury blackcurrant blocks showed that soil health under the bushes was surprisingly poor, for a perennial crop. Older blocks were worse than younger ones, indicating that soil condition declined under blackcurrant management. This was because of low organic matter inputs–not enough food for soil microbes and earthworms, whose activities maintain and improve soil health. The situation under blackcurrants was a vicious cycle. Soil quality restricts root growth leading to shoot growth, meaning fewer prunings/leaves go back to feed the soil, which leads to worsening soil conditions. Many of our pre-emergent herbicides are hard on earthworms, both in terms of direct toxicity and in terms of bare soil providing no food for the creatures. Compaction from farm operations doesn’t help either.

Soil quality can be wrecked quickly with tillage and compaction, while the remediation process is quite slow. Increasing organic matter inputs is the main way to improve soil quality (while simultaneously avoiding compaction).

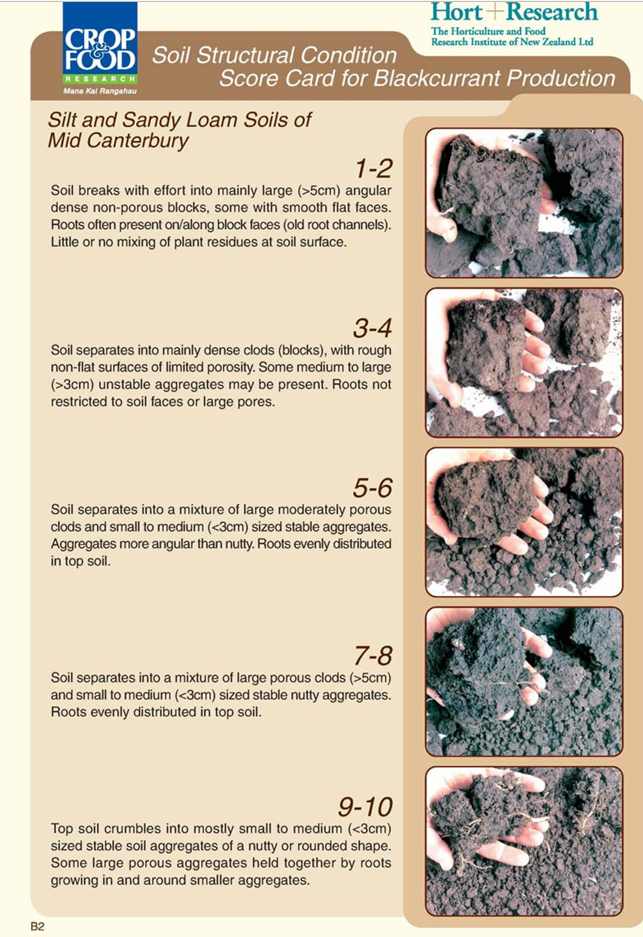

The team measured all kinds of soil parameters and in the end decided that a visual assessment of soil crumbliness was as good as anything for rating soil health. A 1-5 Visual Soil Assessment (VSA) scale was developed, where 5 is excellent and 1 is the worse.

Recently I’ve been having a look at the soil quality in a few blackcurrant blocks, trying to “get my eye” in to using the VSA scale.

This first (left) sample I’d call a 5. There were so many blackcurrant roots in the shovel of soil that I couldn’t actually separate them from the plant, and when I tried the soil crumbled away in nice loose aggregates. The plants growing here were planted 10 months ago, and had grown 600mm in their first season. Clearly good soil structure was not the only component of this healthy picture; the plants had also received timely fertilizer and irrigation, as well as good weed control. But soil structure was supportive of all that good management translating into good root and plant growth.

The second sample I’d call a 2. There were a couple earthworms sighted, but there weren’t a lot of fine roots to be seen, and the soil was hard to crumble. Plant growth in this block had been less than desired for years, and while a lack of nutrients have had a part to play in this, the soil structure has also not supported good root growth.

Below is the visual rating scale developed by the research team in 2004.

In conclusion, have a look at the structure of the soil under the blackcurrant bushes in your best and your worse blocks. Where improvements are required, think about how to add organic matter. Growers are great with equipment—how can we push row centre mowing residues and prunings back under the bushes to feed the soil, so it can better feed the blackcurrants?