© 2025 Berryworld, All Rights Reserved

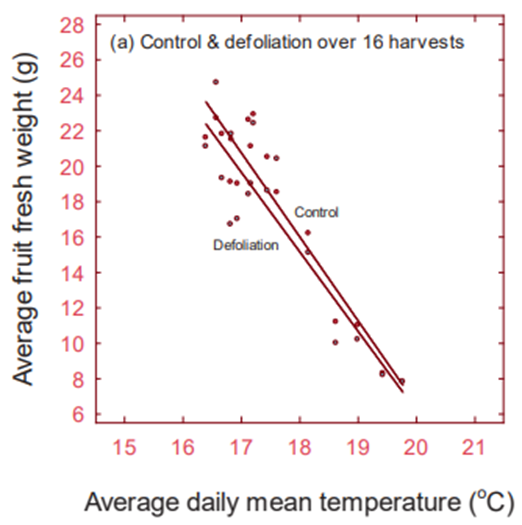

I recently ran across a study done by Christopher Menzel of the Department of Ag and Fisheries, working in Southeast Queensland, Australia.

In Queensland they see the berry size decrease from an average of 25g in July to 8g by October (using Festival, a short-day Florida variety bred for winter production). Christopher set out to determine if lightening crop load (removing flowers) can make the remaining strawberries bigger.

He found that thinning out flowers can make the remaining berries a very marginal 1-2 grams bigger, but thinning flowers caused the number of marketable (berries over 12g) and overall yield to decrease by 15%. Flower thinning clearly wasn’t a win.

Even more remarkably, they found that for every 1°C that the average daily temperature rose over 16°C, the berry size decreased by 4.5g. That’s a dramatic penalty for high temperatures.

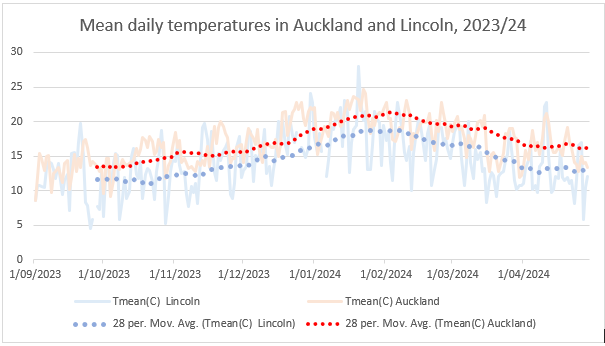

That got us thinking about the small fruit size we see starting in mid summer in Auckland, and wondering how many degrees over 16°C our daily temperatures average.

This graph is remarkable to me. Orange dotted line shows Auckland’s 4 week rolling average temperature (average of the 28 days prior), and the blue dotted line shows Lincoln’s. In the background the very light blue is Lincoln’s average daily temperatures, and the orange is Auckland’s. The four week rolling average line helps to visualize a longer-term average, over a time period similar to flower differentiation happening deep in the crown.

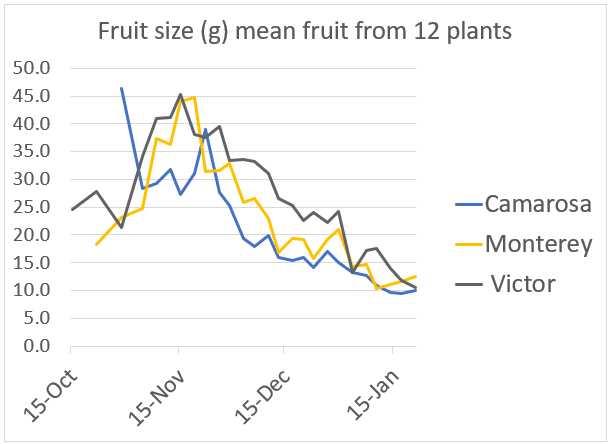

Auckland’s average daily temperature reached 20°C in the third week of November, and 7 weeks later (mid January) fruit size is around 10g/berry.

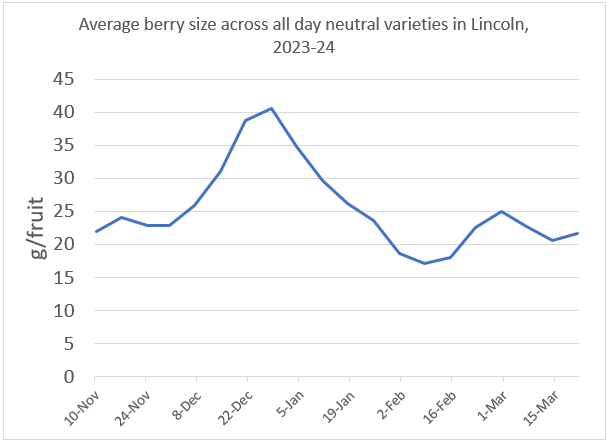

Similarly, we see a size decline in Lincoln’s berry size to about 17g/berry after hot weather in December and January.

Interestingly, the berry size never dipped as low in Lincoln as it did in Auckland, and the temperatures averaged 2-3 degrees lower in Lincoln.

Temperature affects flower induction, the microscopic process happening at the meristem where flower primordia are formed. The potential fruit size is capped way back at the primordia stage, as this stage determines how many primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary flowers are formed, and the number of potential achenes per fruit.

We measure berry size and yield, but when was the microscopic flower induction process happening to start those berries? How long prior to fruit harvest does the induction of the relevant flower take place?

The Queensland study worked on the basis of 7 weeks. In cooler climates, we might logic the stages to take quite a bit longer; 4 weeks from pollination to ripe fruit, 3 weeks from flower bud emergence to pollination, and another 5 weeks of flower differentiation happening deep in the crown1….all that adds up to 12 weeks.

Obviously, average daily temperature is only one aspect of heat. Does it only take one hot day to influence flower bud primordia? What if the nights are cool but the days are hot? What about sunlight intensity, and day length? We haven’t even begun to question nutrient and watering regimes.

Clearly there are more questions to be pondered, but temperatures are one inescapable driving factor.