© 2025 Berryworld, All Rights Reserved

Landcare Research has been working on a piece of thrips control this summer. It’s the second part of a project which is funded by SGNZ, with support from the Lighter Touch program and Barkers.

Zhi-Qiang Zhang and his graduate student Xintong Li (Auckland University) completed the first part of the work earlier in the summer, a landscape survey to determine where thrips were building up their populations before infesting strawberries. A summary of those results can be found at https://berryworldnz.wordpress.com/wp-admin/post.php?post=1391&action=edit

Auckland landscape survey lessons:

In west Auckland, Western Flower thrips (WFT) build up early in the season on strawberries themselves, with higher numbers in strawberries than in any of the surrounding vegetation. We can’t blame our thrips problems on the neighbours… Intonsa thrips (a species closely related to WFT) are also present from early on in strawberries, starting at low levels in November and becoming numerous in strawberry flowers for a short time in late January/early February, but then giving way to the dominant WFT in March. Both species also have high numbers in white clover starting in December, and this clover could be serving as a “reservoir” for thrips, allowing them to quickly repopulate strawberry fields after control measures.

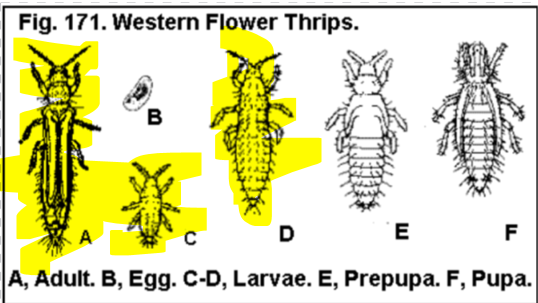

Thrips life cycle:

Before we go into the summary of the later work, let’s review the thrips lifecycle. An adult female thrips can make over 200 eggs, which she inserts inside leaves and stems. Eggs are protected from both predators and insecticides. After hatching, the next two life stages are called “nymphs,” (first and second instars). A “prepupa” and “pupa” come next, and both these are non-feeding stages that usually live in the soil, where they can’t be reached with typical insecticides, but can be eaten by soil-dwelling mite predators and nematodes. In warm temperatures (25-30°C) it only takes a week or two to go from egg to adult, so the populations can explode. Half of the thrips are in a protected life stage at any given time, and adult females can live for a month. While these thrips can survive on foliage, both intonsa and western flower thrips prefer to feed in flowers, where the pollen provides a rich protein source.

While the project originally intended to focus on Intonsa thrips, Western Flower Thrips were added, given the result from the earlier field and landscape survey that showed Western Flower Thrips is the primary pest in west Auckland strawberries.

Predator feeding tests in the lab:

Lab-based feeding tests are one of the early steps in biological control development. Predators are placed in petri dishes and given a known number of pests, and their appetites measured over a short window. These lab tests were not part of the original project scope, but some of their extra results are reported here.

One of the challenges of predator-control of thrips is that the mite predators which live on leaves can only eat nymphs. The project team detailed the appetite of several commercial and non-commercial (NZ native) predatory mites, and showed that the NZ commercial ones (Neoseiulus cucumeris and Amblydromalus limonicus) had the biggest appetites, and greatly preferred the 1st instar nymphs. Both ate about 6 nymphs in 24 hours, and could subsequently lay eggs after that feeding. The egg laying is important because for a predator system to be commercially workable, the predators have to successfully build their population within the crop.

Two insect predators’ appetites were tested, a green lacewing larva (Mallada basalis) and a predatory bug (Buchananiella whitei). Both prefer 1st instar nymphs, but both eat plenty of second instars and even have the ability to eat a few adults. They have bigger appetites, in the range of 13 thrips for green lacewings and 9 thrips for predatory bugs in 24 hours.

Predator tests in the greenhouse:

The real test to a predator being a functional tool in a commercial system is how it does on strawberry plants. The team set up little insect cages at the Landcare Research site in Auckland, each with 4 strawberry plants and a controlled release of 40 thrips adults. The thrips were given a week’s head start to establish before predators were released.

The first challenge the team faced was that thrips establishment after release into the strawberry plant cages wasn’t very good, especially intonsa thrips establishment. It’s ironic, given the success thrips have on commercial strawberries! It does highlight that thrips are primarily a flower problem for strawberries, and these plants were struggling to maintain strong flowers in the heat and shady conditions of the experimental shade house. The results also seemed consistent with the field surveys which showed that Western Flower thrips were the dominant pest (they established better), with Intonsa having a relatively transient peak.

One significant observation from the first cage trial was that lacewing nymphs were never found after the initial release, not even once. Upon discussion with IPM Technologies (Paul Horne, Australia), he corroborated, saying that for some reason, green lacewings don’t seem to establish in covered cropping situations.

The team repeated the experiment after moving the plants to a sunnier and more temperature-controlled greenhouse. In this second experiment, focusing on WFT and the insect predators, the predatory bug decreased the thrips population but the lacewing did not.

The preference of both the mite predators and the insect predators for young instar nymphs highlights that successful thrips-control programs must be focused on early establishment of predators to maintain low reproductive success of thrips, rather than a focus on predating thrips adults.

We believe our next step to progress getting success with predator-based thrips control in NZ strawberries is an extension project where we get very hands-on advice, frequently and in-season, to support implementation of a successful predatory mite-based (cucumeris) thrips control program. IPM Technologies out of Australia has walked the Australian strawberry industry through the transition from pesticide-based thrips control to predator-based thrips control, and has the proven experience to do this for the NZ industry. In their case, insecticides had failed due to insecticide resistance, and they made the transition before they had an effective commercially-available insect predator (Orius), using just cucumeris.