© 2025 Berryworld, All Rights Reserved

When the target is a flower…

We had spent the first part of the morning exploring spray coverage with water sensitive papers (see https://berryworldnz.wordpress.com/2024/10/13/hitting-the-target-part-1/). After a tea break, the grower made an astute comment:

“If we’re after botrytis, leaf coverage isn’t really the important bit. We want the flowers, and we can’t really clip water sensitive papers to a flower.”

So true. Out came the powdered blue food dye.

Side note: I bought 4 different blue food colourings before I found one that was strongly coloured and dissolved well in water. I settled on food grade “Brilliant blue powder” from HawkinsWatts, which can be purchased by the kg.

Spray coverage of flowers is illustrated stunningly with blue food dye.

This early in the season, the spray coverage of flowers was pretty good. They are generally facing upwards and the canopy isn’t very dense.

In the case of botrytis, where sporulation on ripe fruit often starts with infection around petal-fall, a very important part of the flower to cover are the stamens. After they shed pollen, they senesce, and they stay attached to the berry. Infected petals can also lead to fruit infection, but at least petals usually dry up and fall off.

If you look a the anthers closely, you can see the fuzzy botrytis sporulation

It turns out that anthers are hard to wet. Maybe the textured surface repels water? Maybe the pollen grains are oily?

To make matters harder, once pollination has occurred and the berry begins to grow, the sepals often curl up around the berry base, hiding the anthers and complicating future spray coverage.

When a surface is hard to wet, we can turn to a whole arsenal of adjuvants that can make a massive difference.

David Manketlow, speaker at the SGNZ winter conference and one of New Zealand’s forefront agricultural spray specialists, talked about wetters, spreaders, and stickers. The array of adjuvant choices is mind boggling.

Basically an adjuvant is a product that enhances the performance of an agrichemical in some way without being a pesticide in its own right. All formulated agrichemicals contain a mix of adjuvants, but sometimes it is useful to make extra adjuvant additions to your spray mix to help enhance efficacy.

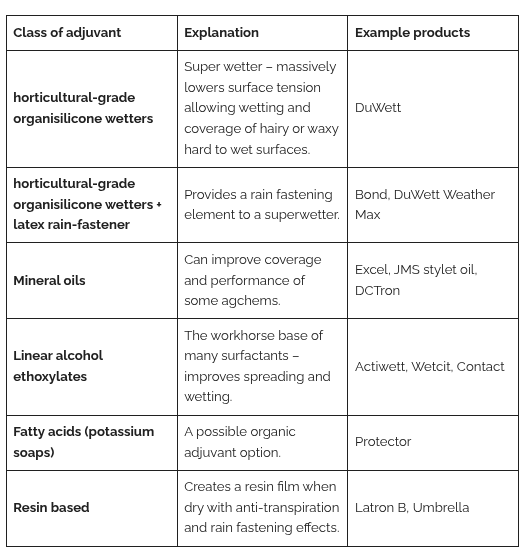

The most common places where addition adjuvants can help are to improve spray wetting, coverage and adhesion. The following table breaks them down into a few common categories.

Clearly, there are levels of complexity within the broad categories of wetters above.

Caution: Some adjuvants increase the penetration and uptake of agrichemicals – especially herbicides. The herbicide superspreader organo silocones (“Pulse” is one example) are dangerous to use with non-systemic horticultural sprays which are safe on plants only if they stay on the outside of the leaf, but cause phytotoxicity if they enter the leaf tissue (Captan comes to mind).

Choosing an appropriate rate is another minefield. We simplified our day by trying David’s favourite flower wetter (DuWett) and a rate he chose for us as a starting point (100ml/100L).

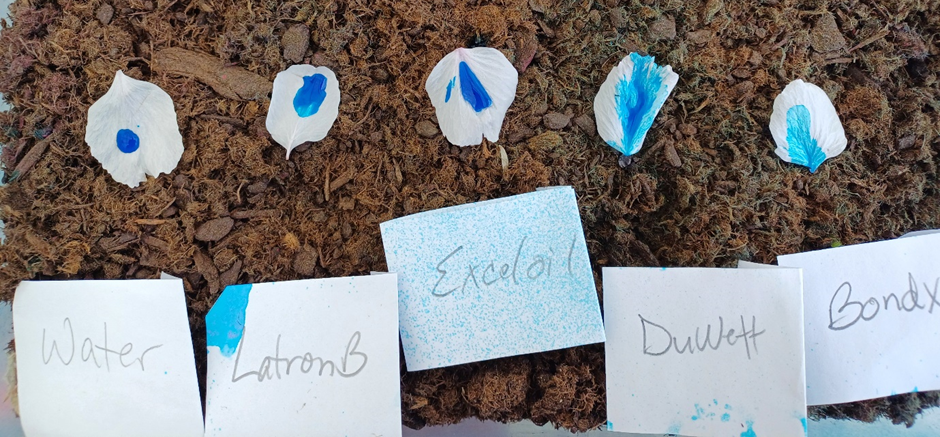

The effect was dramatic.

Notice that we even managed to get some blue to stick to the stamens when DuWett was added.

One way to see the effect of a wetter is to mix it with the labeled rate of water and drop it onto the target plant tissue. Here we did this with a couple of the common adjuvants on flower petals.

The effect of several common adjuvants on water drops on flower petals.

If anyone has ever tried to work out the proper rate of DuWett (or Bond) from its label, you’ll know how truly bewildering it is. This is because the adjuvants already formulated into different agrichemicals can be antagonistic (but are sometimes synergistic) to the adjuvant you add.

The rate also gets complicated by your chosen spray application volume. The adjuvant loading in a dilute spray mix (using the product label rate per 100 litres of tank mix) will be lower in terms of mL adjuvant per L spray than in a concentrate spray mix. A concentrated spray mix maintains the same active ingredient per hectare, but this is delivered with less water as a carrier, and typically requires more wetter/L spray.

The key thing to understand here is that the amount of spray volume it takes to cover the target spraying surface area of anything from an avocado tree to a strawberry plug is highly variable, and water rates can go down if air assist means that air is part of the delivery vehicle. Higher-than-optimal rates of wetter with higher-than-optimal rates of water causes the spray solution to drip off leaves, actually decreasing the amount of chemical that sticks on to the leaf surface.

It is not easy. The key is to observe how your spray deposits behave on the plant parts that you are trying to target with spray.

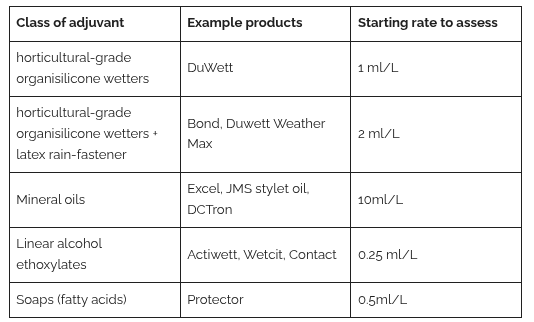

My shortcut was to ask the expert (David Manktelow) what rates to start with for DuWett given the target is a strawberry flower. Use the rates from the labels for the other groups, assuming that the hairy undersides of strawberry leaves are classified as “hard to wet.” The following are reasonable starting points.

Action items:

Given that wetter rates are a moving target, how do you assess if you have too much wetter or too much water?

The aim, after a spray application, is to get as much of the spray as possible to be retained on the actual spraying target. Much of the spray applied will be deposited on leaves – and this is fine if they are the target.

Thankfully spray coverage is very tangible! We can optimise coverage and efficacy by observing how spray behaves on the plant and tuning the practices accordingly.

Many thanks to David Manktelow for his revision and additions to the article above

Many thanks to the technical reps at Fruitfed (Craig Lamb, Rob Wards, Harrison Still) for sourcing samples of wetters for us to play with.